It’s like Mount Rushmore. Only sinister. And missing Lincoln. And with Franklin. And also missing Roosevelt. Also, surrounded by sparking lightning. Though, to be fair, that might also happen on the regular Mt. Rushmore, I’ve only ever been there the once and might just have missed it.

The Bioshock series has spent three games delving into a specific idea in each. The first dove into Objectivism and was very successful at it. The second game dug into something like Collectivism and was less successful at it. Bioshock Infinite, however, digs into something more amorphous.

At first, it seems like Infinite is going to be about religious fundamentalism as a governing philosophy. But, that it quickly becomes clear that religion is just part of a greater whole. In truth, much of the beginning of the game is about showing the inherent hypocrisy in the American mind at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries. We see a happy, religious, and invariably white cast of Real Americans.

So real are these Real Americans, that they’ve begun a sort of idol worship of Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. We’re quickly shown how this veneer of a happy society has underlying troubles. Racism is rampant and blatant. Blacks and Irish are an oppressed lower class who exist only to perform the menial and low skilled work that keeps the economy of the floating city Columbia humming. There are even nods to the worker’s rights movements of the period. Eventually, there’s even open warfare between the “Founders” and the revolutionaries seeking equality.

But even that conflict isn’t what Bioshock Infinite is really about. When you dig deep down, what you find is a story about fatherhood and redemption. Booker DeWitt, our protagonist, is sent to “bring [them] the girl and wipe away the debt”. He finds Elizabeth–the girl–kept locked away by her father. As the game progresses, Booker reveals that he lost his wife in childbirth and has no children. Perhaps because of this, he slowly grows to become something of a father figure to Elizabeth–protecting her and fighting for her–even as his original mission slips away from him.

There are some things that have been mainstays of the Bioshock series since its inception. The Big Daddies and Little Sisters are the two most recognizable and iconic elements–especially visually–of the series. Both are absent here, but they have their spiritual successors, I think. The endless progression of Little Sisters has been replaced with Elizabeth–your charge. The Big Daddies meanwhile have been replaced by the Songbird, her protector. While there is visual similarity, especially in the Songbird, I think this break is largely a good decision for the series. Bioshock 2 seemed to lean too heavily on the original for its plot and setting. This made it feel bolted on due to how complete the story of the original Bioshock was. The clean break that was made with this installment liberated them from some of the burdens that they had been carrying since the first Bioshock.

As a game, there’s truly little to say about Bioshock Infinite. The combat is competently executed, just as it has been for the last two games. The encounters are mostly well designed and the difficulty progression is reasonable. The weapon and

As a game, there’s truly little to say about Bioshock Infinite. The combat is competently executed, just as it has been for the last two games. The encounters are mostly well designed and the difficulty progression is reasonable. The weapon and plasmid vigor combinations are mostly unchanged, though they are a bit unbalanced. Most notably, the very first one unlocked can quickly become a one-attack kill on most non-elite enemies, even on the hardest difficulties. All this is not to say that there’s anything bad about the combat, just that the changes are mostly evolutionary.

The real strength of Bioshock Infinite is its story. Watching the evolution of Booker and his relationship with Elizabeth is worth the cost of admission alone. I would say that Bioshock Inifinite is certainly better than Bioshock 2 and may even be better than the original Bioshock. It is certainly not a game to be missed.

The real strength of Bioshock Infinite is its story. Watching the evolution of Booker and his relationship with Elizabeth is worth the cost of admission alone. I would say that Bioshock Inifinite is certainly better than Bioshock 2 and may even be better than the original Bioshock. It is certainly not a game to be missed.

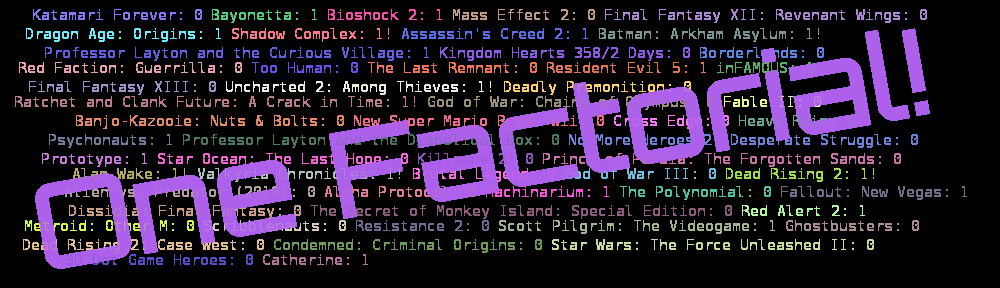

Bioshock Infinite: 1