Over the weekend, I finished up my play through of Mass Effect 3. Being a blockbuster franchise, I’ll be dispensing with the description of what it is. Now, the real trick in reviewing Mass Effect 3 is that, based on murmurings that I’ve heard round the Internet, the game may be vastly different to different players. Given such, anything I say about the plot should probably be taken as just one view into a multifaceted work. And finally, before I finish my disclaimers, I should say that there’s going to be plot talk about the two predecessor games and some about this final one. You’ve been warned.

For me, Mass Effect 3 began with Shepard under house arrest on Earth, after the events of the Mass Effect 2: Arrival DLC mission pack. The Reapers have finally invaded and decided to hit Earth first and hard. Honestly, given that the only person in the galaxy to kill a Reaper was a human, this seems a fair way to get started. With the fight on Earth hopeless, Shepard is sent off world to find some way, any way to fight back against the seemingly unstoppable Reaper threat.

After locating the plans for a MacGuffin capable of defeating the Reapers, Shepard instantly launches into a galaxy spanning campaign to recruit allies to both build it and hold back the Reapers advances to give time for said MacGuffin to be built. This section of the game is where it really shines. Unlike many other “save the world” or “save the universe” games, Mass Effect 3 manages to give the struggle real weight. People who matter die and decisions have real consequences. Most notably, the game often forces you to choose between having the best possible force now and trying to ensure a stable post-Reaper galaxy with the caveat that winning with anything less than everything (or even with everything) isn’t assured.

From a gameplay perspective, Mass Effect 3 follows very closely on Mass Effect 2‘s model. Nothing of great substance has changed, though weapon modifications are back from the original Mass Effect. Of course, the gameplay in Mass Effect 2 was extremely solid, so this isn’t a major issue. Given the nature of the story, however, there seemed to be less diversity in enemy opponents this time around. I wonder if that might make certain classes weaker this time around than previous.

My main irritation with the game was the available endings. I didn’t dislike the choices themselves–I’ve written a large analysis of them elsewhere on the site–what I didn’t like is that I was forced to make a choice and then was not shown the implications of that choice. This same problem appeared in Deus Ex: Human Revolution, though I would argue it is worse here.

Nevertheless, the sheer strength of the story in the mid-game largely makes up for the lack of denouement, at least to me. It is rare that a game can make me feel real emotion about it’s characters, but Mass Effect 3 did. It may also be the only game in which a forced loss didn’t feel like it can from stupidity being the only option.

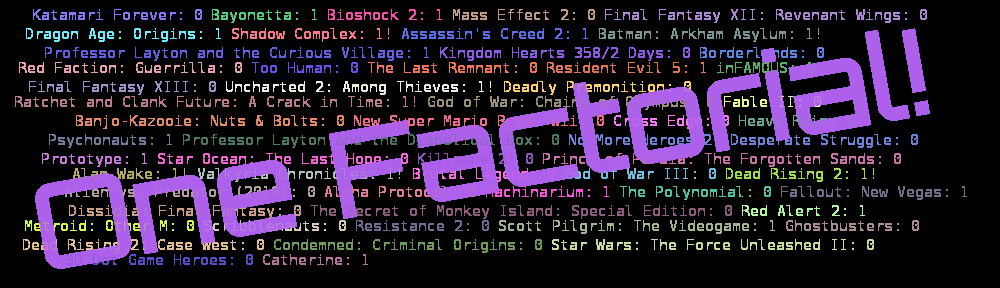

Mass Effect 3: 1