Sometimes, it takes days and days to play through a game and get a feel for its strengths and weaknesses. Sometimes, however, it takes hours. Usually, as in the case of Atom Zombie Smasher, this is a bad sign.

In this middle of an alternate history version of last century, zombies have sprung up. As the leader of a society, you must try to save as many people as possible while fighting off the zombie threat.

The “meat” of Atom Zombie Smasher is the rescue/attack portion of the game. In it, you are given a handful of “squads” with which to repel increasing hordes of zombies. While you’re trying to kill the zombies, you must also try to evacuate civilians. If zombies (represented by purple dots) run into the civilians (represented by yellow dots) then there are suddenly more zombies and fewer civilians. This is, obviously, not a good thing.

The “meat” of Atom Zombie Smasher is the rescue/attack portion of the game. In it, you are given a handful of “squads” with which to repel increasing hordes of zombies. While you’re trying to kill the zombies, you must also try to evacuate civilians. If zombies (represented by purple dots) run into the civilians (represented by yellow dots) then there are suddenly more zombies and fewer civilians. This is, obviously, not a good thing.

There are a fair number of different kinds of squads which allows for somewhat interesting interactions. Squads themselves level up in various ways, becoming more useful as the game goes on. Although the zombies are the primary enemy, the game also has a constant ticking clock in the form of a day-night cycle. During a mission, whenever a day ends, a huge wave of zombies inundates the map. This is usually a tactically intractable situation making the day-night changeover a hard cutoff for missions.

There are a fair number of different kinds of squads which allows for somewhat interesting interactions. Squads themselves level up in various ways, becoming more useful as the game goes on. Although the zombies are the primary enemy, the game also has a constant ticking clock in the form of a day-night cycle. During a mission, whenever a day ends, a huge wave of zombies inundates the map. This is usually a tactically intractable situation making the day-night changeover a hard cutoff for missions. The game also has a strategic component to go along with the tactical one. This part of the game allows you to choose which territories to attack. As the game progresses, more and more zombies spawn on to the strategic map. This forces you to choose your battles to try to mitigate the spread before any particular area becomes overrun.Although AZS has lots of interesting ideas, the game itself seems to suffer from cripplingly bad balance. In the basic gameplay mode, squads are assigned (seemingly) randomly. This might lead to you having to try to carry out a mission using only barriers, a couple of landmines and maybe an artillery piece. Worse, while the game does allow squads to level up and become more useful (and thus make the higher level missions more possible), the speed of leveling up in incredibly slow and the progression doesn’t carry over from one game to the next. Of course, since the squads are assigned randomly, you might not even be able to use them once you’ve leveled them up.

The game also has a strategic component to go along with the tactical one. This part of the game allows you to choose which territories to attack. As the game progresses, more and more zombies spawn on to the strategic map. This forces you to choose your battles to try to mitigate the spread before any particular area becomes overrun.Although AZS has lots of interesting ideas, the game itself seems to suffer from cripplingly bad balance. In the basic gameplay mode, squads are assigned (seemingly) randomly. This might lead to you having to try to carry out a mission using only barriers, a couple of landmines and maybe an artillery piece. Worse, while the game does allow squads to level up and become more useful (and thus make the higher level missions more possible), the speed of leveling up in incredibly slow and the progression doesn’t carry over from one game to the next. Of course, since the squads are assigned randomly, you might not even be able to use them once you’ve leveled them up.

The biggest problem though seems to be the strategic map. The whole progression of the game is based on a scoring track. Evacuating civilians and capturing towns get you bonuses. The issue is that, every turn, the zombie faction gets more free units than you can reasonably be expected to deal with. This gives them more points which makes it harder and harder to keep up.

Now, it may be that extended practice and experience might help mitigate these problems. It might also be the case that I might just not be a solid enough tactician to make the game tractable. I’m willing to accept that either of these might be the case. Unfortunately, the frustration that the perceived (if not actual) balance issues cause mean that I have no interest at all in exploring these possibilities.

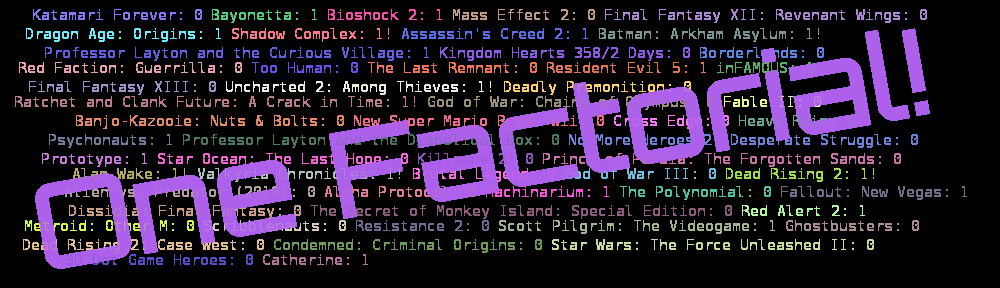

Atom Zombie Smasher: 0